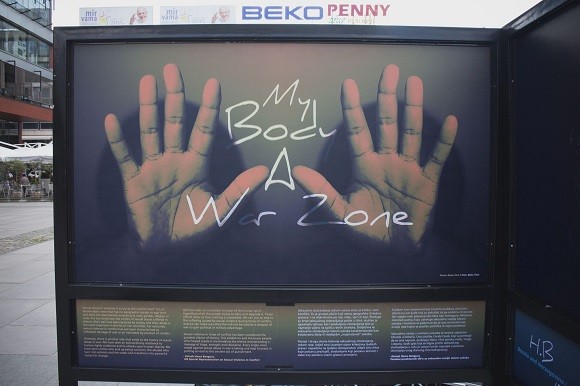

My Body: A War Zone aims to raise awareness of sexual violence in conflict. Image credit: Clara Casagrande.

My Body: A War Zone aims to raise awareness of sexual violence in conflict. Image credit: Clara Casagrande.The exhibition, developed by PROOF: Media for Social Justice in partnership with the Sarajevo-based Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC), aims to bring individual stories of injustice to the broader public, in an effort to overcome the silence and stigma associated with crimes of sexual violence. The exhibition also intends to help replace the culture of impunity for sexual violence with one of deterrence.

Award-winning photographer Paul Lowe opened the exhibition. “Displaying these stories in such a visual and public manner is a strong approach to overcoming the stigma associated with such crimes,” he said.

British Ambassador Edward Ferguson added: “We must all do more to tackle this problem of wartime rape, to support survivors and to bring criminals to justice.”

Many cultures, one demand: justice

In the exhibition, Bosnian Midhat Poturović plays with shadow, light, and reflection, symbolising the plight of survivors who are struggling to step out of the dark with their stories.

Blake Fitch reveals the intricacies of a woman’s hands, conveying a story of shame and fear but also resistance and strength.

Nayan Tara Gurung Kakshapati, from Nepal, depicts reflection and remembrance, while Kenya-based photographer Pete Muller’s photography embodies the vibrancy of Congolese culture.

During the unveiling ceremony, Poturović explained that the Balkans has a history of repeating its past mistakes. “Documenting and preserving these powerful stories for future generations can help us to avoid a recurrence of such atrocities down the road and can serve as a tool to end impunity for perpetrators.”

In an emotional address, one of the survivors pictured in the exhibition, who survived rape, torture and detainment as a teenager during the Bosnian war, highlighted the ongoing struggle of women victims of war. “We have been left to our own devices on the margins of society, with no options for psychological, financial, or legal support.”

Sexual violence as a weapon of war

The United Nations estimates that between 20,000 to 50,000 people, predominantly women, were raped during the 1992-1995 war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the most extreme cases, special camps were established where women were forcibly held and systematically raped over the course of several months. Although women were more likely to fall victim to this sort of institutionalised and systematic discrimination, it is important to note that men were also subjected to sexual violence during the Bosnian war.

“To this day, those who committed such evil against me are walking free and I cannot return to my home.” – O.D., Bosnian survivor. Image credit: Midhat Poturović.

“To this day, those who committed such evil against me are walking free and I cannot return to my home.” – O.D., Bosnian survivor. Image credit: Midhat Poturović.Unfortunately, Bosnia and Herzegovina is just one example of widespread instances of sexual exploitation during conflict. But the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina differs from other cases, in that it resulted in a monumental step forward in defining international humanitarian law. In February 2001, for the first time in human history, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) recognised rape as a powerful tool of war, used to intimidate, persecute and terrorise the enemy.

In the judicial proceedings that followed, the ICTY enabled the prosecution of sexual violence as a war crime, a crime against humanity and genocide. Despite such progress in the field of transitional justice, sexual violence continues today. Its causes and consequences must be addressed.

Breaking the taboo and empowering victims

By placing the exhibition in front of the BBI Center, one the Sarajevo’s busiest areas, PCRC aimed to bring these stories into the public arena in an effort to break with prevalent practices of victim blaming, and the silence that often surrounds rape.

Including the general public in the dialogue on post-war justice is an important step in demanding accountability from the perpetrators and breaking the taboos associated with crimes of sexual violence.

Most importantly, exhibitions like My Body: A War Zone have the potential to empower victims to speak up and transform from being objects of violence to active participants in the struggle for justice.

Paying testament to the women who came forward to share their experiences with the world, PCRC’s project developer Tim Bidey brought an end to the opening ceremony of the exhibition.

“Without your bravery, all that we are talking about and trying to achieve today would not be possible.”