The relationship between Istanbul and Armenia is key to politics in the Caucasus (image: Hector Garcia)

The relationship between Istanbul and Armenia is key to politics in the Caucasus (image: Hector Garcia)The relationship between Turkey and Armenia is in deadlock because the countries have competing demands. For instance, the official stance of the Republic of Armenia is that a genocide took place in 1915, and that this genocide should be internationally recognized. On the other hand, Turkey denies that genocide occurred. In 1915, 800 Armenian community leaders were executed and between 1915 and 1923, 1.5 million Armenians died as a result of deportation.

In 1991, Turkey recognised the independence of Azerbaijan, a country which has a difficult relationship with Armenia because of Nagorno-Karabakh. The problem began in 1988; Armenia says that this region belongs to Armenia and that there is a large Armenian population there. War broke out shortly after independence and during the conflict, over 200,000 ethnic Armenians were deported from Azerbaijan, and 200,000 ethnic Azerbaijanis from Armenia. Retaliation and violence ensued from both sides.

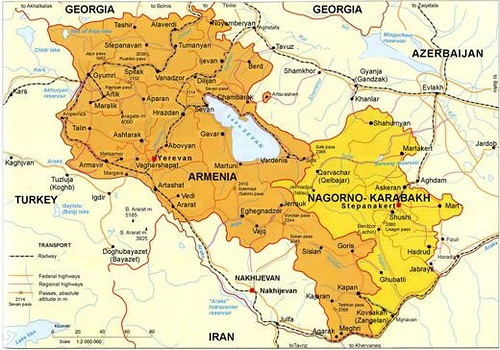

Part of the Caucasus, showing the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh (image credit: Narek)

Part of the Caucasus, showing the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh (image credit: Narek)At the same time, Turkey applied a trade embargo against Armenia in 1993, seen by the international community as a result of Turkey’s relationship with Azerbaijan. Their close relationship caused tension with Armenia, and “The unresolved Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh still risks undermining full adoption and implementation of the potential package deal between Turkey and Armenia on recognition.” The problem increases political conflict and distrust. The most important problem is the "enemy image" Turkey and Armenia have of each other, with all parties having a tendency to demonise the other side. '"Our side" is righteous and justified in doing what it is doing, whereas "the other side" is inherently aggressive and acts the way it does because "it has always been like that".

However, the unsettled relationship between both countries has led to the emergence of various civil society dialogue and peace organisations. These channels create peaceful milieu instead of mistrust and misperception. Track two diplomacy has become influential, with reconciliation commissions, think tanks focusing on regional security, economic cooperation and business partnerships all working together. During the last decade, the significance of civil society has become much more visible, integration with the west has been consolidated and the environment has allowed for the development of new initiatives, including the use of EU funds and liberal transformation.

The main dialogue efforts were launched with the project “Support to Turkey-Armenia Rapprochement”, which aimed to hold policy and media discussions with the participation of media figures, opinion makers and former officials. Workshops, conferences and projects were organised to generate personal interaction between different actors in society. Putting aside stereotypes, beliefs, values and perceptions, they used dialogue to cross otherwise closed borders. Grassroots diplomacy can be an influential instrument for building peace. Their projects demonstrated tolerance, respect, interaction and cooperation, bringing participants together and organising exhibitions, music festivals and student exchanges which can be more powerful for a crucial sector of society: young people, those who will be columnists, politicians, teachers and so on in the future. They constructed new, more positive images instead of the different issues and parties involved.

For peace, the sides began to learn to work together by integrating at individual and civil society level. They discussed their relations, the border issue and how to build cooperation and respect. Oral history kept the human dimension in discussion. This method enriches historical perspectives, perceptions and beliefs, and provides a critical perspective for historical knowledge. When they share their common pain on the same platform, different parties can understand the "other". Civil society leads to friendship, because it allows people to know others, to live with them. And living together is significant, because there is an Armenian community in Turkey and, because of the historical experience, they can face hate speech and discrimination. In domestic and foreign policy, the situation of relations remains very crucial. The only way for lasting peace and a borderless region is real integration, with these small but effective steps of mobility projects and putting participants at the core of activities leading to new values and a new understandings.

To know each other, civil society has aimed different communication methods at knotty historical discussions, many succeeding with an often powerful realisation of mutual respect, tolerance and benevolence; after their meetings, journalists reported that “sides broke into tears when they were leaving.”

“During our communication and interaction, each of us has so-called “culture studies” which is important for all of us, but we do not talk too much about it, usually only in silent observations. During our communication, however, we discovered much about each other’s culture and the phrase “we also have it” became the most common phrase among us, and we took for granted that if we said: “We have this,” our Turkish friends would say in turn: “We also have it” or vice versa. Recently a funny incident occurred: we were tasting guhta (biscuits), and our Turkish friends said: “This is really tasty,” an Armenian friend asks: “Don’t you have ‘guhta’?,” the Turkish one responds: “No” and the Armenian shouts with hands up: "Yeah! Finally! ‘Guhta’ is only ours… I can now say for sure that ‘guhta’ is Armenian."

Turkish-Armenian relations remain in deadlock at the state level, but this does not mean that both countries cannot engage in their rapprochement. Civil society experience has proved their will to be part of confidence building.