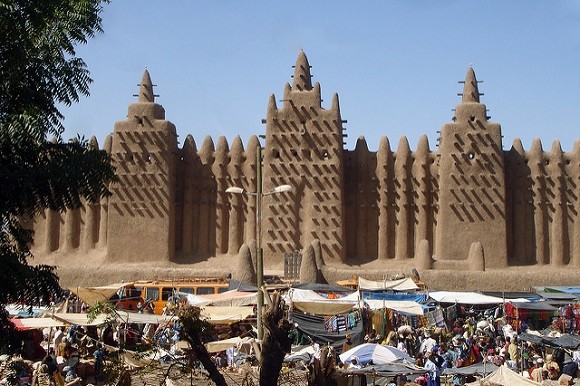

from Mali and elsewhere in Africa have sought to start new lives in Europe.

from Mali and elsewhere in Africa have sought to start new lives in Europe.Image Credit: Carsten ten Brink.

Or consider Kamal, from the Nuba Mountains in Sudan. One day, the massacres that have been raging silently across the country come to his door. So he escapes, leaving his home, his village and his life behind. The Sudanese authorities are deeply involved in this violence, which has been taking place for decades – but they might now receive surveillance support from the EU. Intended to stop migrants passing, will it not end up being used against its own citizens?

In order to stem migration from Eastern Africa, the EU is preparing deals combining aid and support to migration management with conditions for African governments to cooperate. Sudan and Eritrea are allegedly among the latest regimes that the EU is finalising deals with. The EU had previously declared its intention not to channel assistance through governments. But in the case of states like Sudan, it might have to. Sudan has a record of falling out with and expelling international aid organisations from its territory. The latest victim is Ivo Freijsen, head of UNOCHA Sudan. The EU’s ‘country packages’ risk emboldening the authorities and strengthening dictatorships.

Where will the money go?

Although the EU plan reports extensively on how to tackle root causes of irregular migration, most of the funds are pledges of earlier aid by the EU and its member states. The historical record of migration expenditure demonstrates that, instead of being spent on root causes, most of the money will go to migration management. This is mainly targeted at governments in support of their border controls. Sudan is already benefitting from a $40 million regional programme to “better manage migration” in the Horn of Africa, under the European Commission’s $1.8 billion Emergency Trust Fund for Africa.

Defeating the purpose: the need to match means and end

On the western flank of Africa, the most notorious irregular routes lead through countries with weak borders, such as Mali, Niger and Libya. The current situation contributes to a profitable market for the infiltration of extremist and criminal groups, including migrant smugglers, who lure vulnerable young people into their business. Providing funds for migration management to government border posts who make a living out of bribes from those groups is not just a waste of money, it can make the EU complicit and do harm.

Focus on those concerned: young people wanting to leave

As long as any support fails to tackle bad governance and corruption, the root causes driving young Africans to leave their homes will not be dealt with. Our research points to these two factors, in particular, as pushing young Africans to migrate. But policymakers barely recognise them. A persistent narrative is that development will supposedly help stop migration. In fact, young people will leave as soon as they have the money to do so. They need not only jobs and security, but a perspective: to be part of building the future of their countries. Which is exactly what the deals might undermine: by working with the old, ruling elites, and exacerbating autocratic and corrupt regimes.

In the decades to come, Africa will experience an unprecedented demographic youth bulge. Millions more young people will need to be accommodated on the continent itself. We should instead focus on helping to create long-term prospects for young Africans. This will require working from their direct community, up to government level, with a politically smart, locally led approach. And working with partners that have leverage with elites and government, so as to effectively address structures currently undermining youth.

In May 2016, an estimated 1,100 people drowned in the Mediterranean Sea. Most of them were desperate young Africans looking for a future. Let us put all our effort into negotiating deals with African governments that would actually offer real prospects to their young citizens. Involving them in shaping the future of their countries would be a good first step. The EU can play a catalysing role in this by developing a dedicated youth for Africa policy. And while borders in the region should be fixed urgently, any support must be managed in a more responsible way, carefully considering potential unintended consequences – such as driving more young people on to the boats.