Away from the media’s focus on Al-Shabaab attacks in Kenya, a deadly conflict involving two Somali clans, Degodia and Garre, has been raging in Mandera County in North Eastern Kenya. While clan conflicts are not new to the area, the intensity of the latest flare up (including deliberate targeting of children and women in violation of Somali social norms in clan wars) raises fundamental questions about the newly devolved system of county governance and its impact on conflict dynamics and peacebuilding architecture in northern Kenya. The Mandera conflict comes on the heels of another conflict in neighbouring Marsabit in early 2014. The control of large budgets and political influence that comes with parliamentary and county government posts has turned competitive politics in the region into a zero sum game. The indigenous conflict management mechanisms have neither the experience nor the capacity to deal with political conflicts. The new county governments and the political and economic largesse that comes with them are, if not managed equitably, likely to further exacerbate existing conflicts in the poor and conflict-prone counties of northern Kenya.

The Degodia and Garre clans have a long history of conflict and violence that are documented even in colonial records. The current conflict, however, began in 2008 following the election of Abdikadir Mohamed from the Degodia clan as the Member of Parliament for Mandera Central Constituency. Mr Mohamed unseated Billow Kerow (current senator for Mandera county) from the Garre clan, the majority clan in Mandera and previous occupants of this seat. This election result had wider ramifications on the politics of Mandera: the political domination of the Garre clan was broken; and the political presence of the Degodia clan was felt.

With the underlying causes of the 2008 conflict unaddressed and with higher political stakes in the 2013 elections - more powerful elective posts under the new county governments as well as the creation of an additional three parliamentary seats following a review of the electoral boundaries in 2010 - it was only a matter of time before a new cycle of violence erupted. Unsurprisingly, the election campaigning was characterised by hate messages, displacement of voters, formation of inter and intra clan alliances and the magnification of resident-migrant dynamics including a political pact between the Garre and Murule clans (these two clans have a history of conflict and this pact was meant to temporarily address this.) Subsequently, the Garre clan not only regained the Mandera Central parliamentary seat, but also won an overwhelming majority of political seats in Mandera including the key posts of Governor and Senator. They also surprisingly won - and this was the main trigger for the current conflict - the new Mandera North constituency in the largely Degodia-dominated areas.

Beyond the clan rivalries and exclusionary politics, the current Mandera conflict also comes against a backdrop of changing peacebuilding architecture in the region. The long history of clan conflicts and the neglect by the state have led to the evolution of innovative and effective local “hybrid” conflict management mechanisms based on the mostly Somali and Islamic traditions of the local communities. The national government and its security institutions have over time become accustomed to the existence and usefulness of these mechanisms. But with the creation of the county governments and the changing nature of conflicts, the effectiveness and impartiality of these local peace structures have been questioned. For example, in the current Mandera conflict, the local peace committees were at best unsure of how to respond to the conflict or at most became hostage to the interests of their clans and political elites. A new national peace policy that harmonises the existing peace infrastructures with the new county governance structures is yet to be fully implemented.

The conflict systems in the region are further complicated by the emergence of new forms of conflict such as terrorism and the problem of radicalisation. The Mandera conflict comes at a time when the attention of the Kenyan state is focused on countering terror attacks from the Somali-based terror group, Al-Shabaab. Clan clashes and communal violence are treated as secondary issues by the security forces, as shown by their slow response to the Mandera clashes. But fears that these clan clashes may pose a threat to the security of the state (and statements by local leaders that Al-Shabaab was involved in the latest clashes in Rhamu are meant to play into these fears) may lead to more violent responses from the security forces.

A sustainable peace in northern Kenya requires a multiple, sustained and complementary efforts at the national, regional and local levels. At the national level, the government needs to urgently implement the National Policy on Peace-building and Conflict Management drafted by the National Steering Committee for Conflict Management and Peacebuilding (NSC) in December 2011. The policy takes a comprehensive approach to peacebuilding in Kenya and recommends new institutional and legal frameworks at national and county levels.

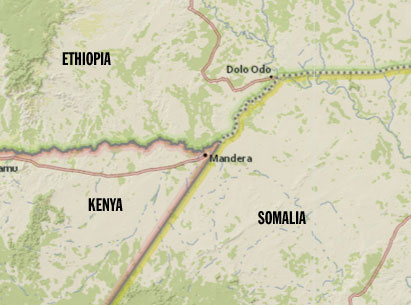

Since militias and arms flows from the neighbouring countries are part of the conflict system in northern Kenya, there is a need for co-ordination of national and county peacebuilding architectures and initiatives with regional ones. These includes IGAD’s Conflict and Early Warning and Response Network (CEWARN), Kenyan military intervention in Somalia, repatriation plans for the Somali refugees and Kenyan-facilitated peace talks in the Somali region of Ethiopia (Ogaden).

At the local level, the President’s appointment of an external mediation team is a welcome move. The mandate of this committee needs to go beyond addressing immediate issues of the conflict. There is also a need to support local capacities for peace deal with political conflicts. Civic education programmes focusing on the rights and responsibilities of communities and civic groups in the county governments should be supported. This should promote practical mechanisms for accountability and redress for communities such as courts, recall of elected leaders, participation in budgetary and audit processes, use of county assembly (“local parliament”) channels among others. This could go a long way towards fostering alternative, multi-clan and non-violent avenues for advancing community interests.

Equally, addressing the realities of conflict and marginalisation in northern Kenya cannot succeed without dealing with the past. It’s the failure to deal with the past abuses and violations that are fuelling new abuses such as those witnessed in the Eastleigh security operation as well as Marsabit and Mandera conflicts. The implementation of the recommendations of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC) report will be key to this. In its absence (the report is pending with President Kenyatta since May 2013), other short-term mechanisms need to be put in place. One such avenue is the empowerment of the newly constituted Independent Police Oversight Authority (IPOA). The Commission investigated and found glaring omissions in the security operation in Eastleigh. The IPOA recommendations on Eastleigh should be immediately implemented and be used as a guideline for future security operations in northern Kenya (as well as the rest of Kenya.)

The northern region has lagged behind the rest of Kenya in the last fifty years due to conflict, poverty and marginalisation. Devolution offers a real chance to address these issues, but conflicts such as those in Mandera and Marsabit represent a risk to real development in the region. A paradigm shift in conflict management and governance is needed for this region to realise the full benefits of devolution.