Building Peace Through Books: A Library Counters Religious Bias

At a time of heightened polarisation in India, local peacebuilders are turning to innovative, community-rooted strategies to resist hate and further inclusion. One example of this is The Community Library Project (TCLP), a network of free libraries located across Delhi - in South Extension, Malviya Nagar, and Sikanderpur - that provide access to books and safe spaces for dialogue, critical thinking, and collective learning.

The idea of the library started in 2014, when a group of college students wanted to create space for open conversations in a country where public opinion has become increasingly polarised. Set up in the premises of an NGO-run school with just a few books on politics and social science, the library was born. What began as a small act of protest has since grown into a full-fledged reading movement with over 14,000 active members. By bringing together people of all age groups, the library encourages open and respectful discussions thus helping build understanding across divides.

“We don’t call ourselves a peacebuilding organization,” Mausam Kamari, Director at TCLP, says with a smile. “But when people read together, question together, and care for one another, peace is what naturally grows.”

TCLP: A Vessel of Peace

TCLP’s core philosophy “Everyone deserves to read” is simple, yet radical.

The project encourages reading and storytelling as tools of resistance, especially among children and youth who experience tense social contexts - such as neighbourhoods affected by religious violence, discrimination based on caste or gender, or where access to safe public spaces and education is limited.

By hosting reading clubs and creating inclusive discussion forums on a range of topics including discrimination, Islamophobia, feminism and identity, TCLP is able to foster an environment where ideas shape relationships and where the act of reading helps communities to challenge stereotypes and build solidarity.

By centring marginalised and minority voices, including Dalits, Muslims, Adivasis (Indigenous), women, and refugees, and encouraging open conversations across caste, class, and religious lines, these libraries have become powerful agents of peace.

“Our libraries are not only places where one can borrow books. These are warm, welcoming spaces where people can come together and share stories, ask questions, and reflect on their place in the world”, says Mausam Kumari, Director at the TCLP.

“At a time when education and open conversation are becoming increasingly difficult, TCLP insists on the right to education and access to books, creating a space for critical thinking,” she adds.

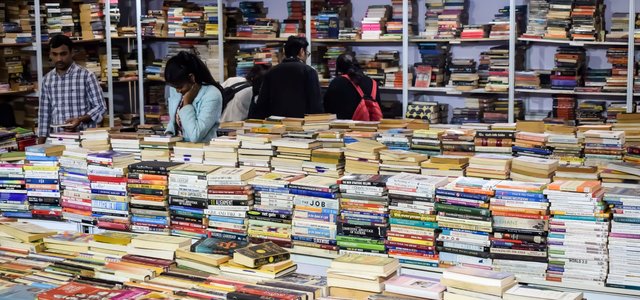

In 2019, the library rented its own space and began operating independently. Today, TCLP runs three physical libraries in Delhi, in South Extension, Malviya Nagar, and Secunderpur and also maintains an expanding digital library managed by a staff of 37 people. These libraries are free, open to all, and run with a democratic spirit. There are no membership fees and no gatekeeping.

“We believe libraries should be part of everyday life, especially in communities that don’t have access to them,” says Sahil, who manages the Malviya Nagar centre. “The goal is not just to promote literacy, but to build a space where people feel seen, heard, and safe. For this reason alone, we give members orientation against Islamophobia, homophobia, etc.”

Importantly, TCLP trains members to become facilitators. Many young people who once came in shy and unsure now lead reading sessions themselves, creating a cycle of learning, leadership, and trust.

For instance, Sahil joined in 2014 when he was just nine years old and had no access to books or education. He was the first school-goer in his family. Drawn in by the storytelling sessions, he began exploring picture books, which soon developed into a reading habit. Today, he manages one of the centres as a community organizer and librarian.

Step inside any TCLP library and you’ll find children lying on mats with picture books, teenagers immersed in novels, and young facilitators guiding discussion groups. The walls are lined with books reflecting a wide range of identities and histories, from Dalit autobiographies and feminist essays to queer literature and Partition (India-Pakistan partition) stories. But it’s not just about the books; it’s the act of reading together that makes the space special as shared reading encourages active listening and mutual respect. When people encounter different perspectives and talk about them openly, it helps break down stereotypes and build solidarity

Each week, TCLP hosts reading clubs where young people explore themes like empathy, freedom, discrimination, and identity. The books often spark powerful conversations like a story about a girl resisting child marriage might lead to a discussion about gender roles at home, while a poem about migration might open up memories of Partition or recent communal violence. These conversations help challenge inherited biases and some said they have become more open to listening to others who are different from them. Some youngsters even reported back saying that they started noticing injustice around them.

“We choose books that reflect the realities of our members,” Mausam says. “Most of our readers come from working-class families. Many are first-generation learners. When they read stories that speak to their experiences, it validates them. It gives them strength. For example, Malviya Nagar has an Afghan refugee population, so we stock many Urdu and Pashto books at that centre.

She adds that the goal is to give people access to diverse literature and help them form their own opinions. “In order to participate in democracy, one should be aware. Reading gives tools to critically think and make informed decisions. It should be a matter of rights, not privilege.”

TCLP also boldly encourages discussions on sensitive topics. Many of the books would be considered “too political” in some schools or public libraries, texts on caste resistance, minority voices, or critiques of nationalism. But that’s precisely the point the library is making that reading, here, is a form of resistance against silence, erasure, and the idea that only certain voices deserve to be heard.

Conclusion

At a time when communal tensions can fracture daily life, TCLP’s work offers vital lessons for peacebuilders globally. It shows that literacy is not only about education but it can also be a foundation for long-term, local peacebuilding rooted in dignity and shared humanity.

TCLP offers a powerful lesson for peacebuilders around the world that one does not always need grand plans or heavy infrastructure to build peace. Sometimes, all that is needed is a room, a few books, and a commitment to listen deeply. In a world where conflicts are increasingly tied to misinformation, fear, and “othering,” spaces like TCLP challenge those narratives by creating room for understanding.