Memory, legacy and a foundation for peace and justice in Lebanon

No criminal is punished in Lebanon. Corrupt governmental officials continue their work unabated. Perpetrators of atrocities committed during the 15-year civil war were granted immunity from prosecution in an internationally-brokered peace deal.

Warlords, some of whom committed massacres and war crimes, have become politicians and granted themselves amnesty. Transitional justice and national reconciliation are nowhere to be seen.

My friend, Lokman Slim, was brutally shot dead four months ago. He dedicated his life to fight what he used to call "state-sponsored amnesia" regarding Lebanon's violent past, marked by systematic impunity, a lack of accountability, political deadlocks, sectarian loyalties and a dysfunctional state. His dedicated career to seek the truth and document stories of peace and war was tragically cut short by a targeted assassination. This was the latest in a series of similar incidents that have occurred in Lebanon since its independence in 1943, including the assassinations of presidents, prime ministers, a grand mufti, politicians, security officials, as well as journalists and activists.

His father, Mohsen Slim, an eloquent lawyer, received death threats when he was representing the family of prominent journalist Kamel Mroueh, who was assassinated in his office on May 16th, t1966. Although the murderer was arrested and put on trial, Slim believed the case was not about condemning the person who pulled the trigger, but rather the political mastermind who recruited him. Unfortunately, it never happened. In fact, the person who planned the attack was protected by Nasser's Egypt, and the crime was justified –even celebrated– by Mroueh's opponents.

Looking back, Mohsen Slim's pleading at that highly intense trial was prophetic. Speaking over 50 years ago, he said that the killer worked for "financial gains, mercenary, profits and the favor of his masters". He added that "justice and freedom are twins, and freedom fades if justice would not avenge the abuses of freedom". However, he was well aware that this case was about politics, and that what he labeled as "political justice" was not in fact a genuine and reliable justice. Even now, this "justice" remains tainted by corruption and impunity.

The criminals who murdered my friend and threatened him when alive counted on that "state-sponsored amnesia". They expected that we would mourn his loss for days, but soon forget about him. They want to rule by intimidation and terror. Our answer is "zero fear", a motto shared by Lokman himself. I write "zero fear", but I am not fooling myself. A non-binary activist confessed to me after the assassination that they felt less secure and feared being targeted. Two days later, at a sit-in to denounce his murder, a journalist told me what I already knew, that Lokman was the bravest of all of us and that he was anxious about our vulnerability. I spoke to him about a suspicious guy going around seeking information and collecting names. He asked me for my name; I stared at him and said nothing.

On March 22nd , UN human rights experts warned that Lokman's murder, "in the event of a lack of accountability, may have a profound chilling effect on freedom of expression in Lebanon".

Assassinations and peacebuilding

Four months after his killing, a foundation carrying his name is now in the making. Its aim is to tackle political assassinations and impunity, and to pursue justice for Lokman. We don't have the luxury of discussing whether it is retributive, transformative or restorative justice. We just need justice!

Although targeted killings are a permanent threat to collective civil safety, democracy and peacebuilding, there is little reliable data about them. According to figures gathered so far by the foundation, 112 assassinations have occurred since the 1950s. Another source counted 125 assassinations since 1943 and 95 murder attempts. The vast majority of these crimes remain unsolved due to "political justice".

The UN human rights experts' letter made public in May called for a review of past investigations into the killings of human rights defenders, activists and politicians, as well as structural reforms to combat impunity and strengthen the independence of investigatory mechanisms.

Some assassinations were already under the spotlight, mainly that of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri. In this case, a special international tribunal took years to issue a verdict condemning a Hezbollah leader in absentia. Ironically, it is believed that Hariri once admitted that some of his ministers were war criminals and should be in jail. I wonder, had they been put on trials and sent to prison, would the course of history have changed? Would lives have been spared?

The Lokman Slim Foundation

Currently, there is an existential challenge facing Lebanese peacebuilders. When a failed state is turning into a rogue one amid extreme political polarization and economic decay - we know we need to continue applying pressure to end impunity, character assassinations and targeted killings seeking to silence dissent.

German journalist and director, Monika Borgmann, Lokman's widow and work partner, thought that peacebuilders have many tools at their disposal, such as "advocacy, publicizing the topic and breaking taboos...Working together with international legal organizations might support our cause", she told me, adding "that the fact that four UN rapporteurs took the case of Lokman's execution is an encouraging sign for the future. In addition, the assassination of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi is in a German court, and so could others. We are exploring all options to go to an international court".

Monika, Lokman's widow, stands by his grave. Photo by Sawssan Abou-Zahr.

Monika's determination to seek justice for Lokman will not wither personally and professionally. She is much more than a loving widow. She spent most of her career tackling the theme of political assassinations and accountability. She interviewed the wives of murdered journalists in Algeria. More importantly, she met the outspoken Algerian journalist Said Mekbel in 1993, a year before his assassination. Their three lengthy interviews seemed like his testament, especially as he reflected on why democracy-seeking activists were murdered. Years later, Monika would get to know Lokman, and his publishing house would issue these interviews in a book.

I have read some of Mekbel's reflections. They are chilling. Monika told me the content of her book was "terrible", and that Mekbel had "a very clear vision". He saw his assassination coming, as did her husband, Lokman. Mekbel, like Lokman, practiced "zero fear". Mekbel had eventually stopped taking precaution measures and wanted them to know he was not afraid anymore.

I didn't dare to ask Monika if she compares Lokman to Said, and herself to Marie-Laure, Mekbel's French wife. Perhaps it is destiny. In fact, it is the topic of assassinations that brought her to Lebanon. She was researching for a documentary on the Sabra and Shatila massacre, trying to decipher a killer's mind. She was introduced to Lokman and the outcome was "Massaker" and a lifetime match.

In Monika's words, "I met Lokman in June 2001, 20 years ago. The fight against the culture of impunity has always been at the center of our thinking and work. Today I'm forced to do it without him and for him". She explained that the foundation carrying his name will therefore work on defying political assassinations and the practice of impunity. Lokman believed, and so does Monika, that standing against impunity is an urgent need for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region to "achieve democracy and a human rights-oriented culture".

The foundation intends to establish a department of lawyers who would advise the families of murdered figures about legal courses of action, "in case other political assassinations happen, inside their country and at an international level", Monika explained.

In parallel, the foundation will have a research mandate focused on documenting political assassinations in the MENA region to establish "a reliable database that sheds light on truth finding, and the legal measures which were taken - or not taken - by the concerned authorities, or internationally". It will publish studies dissecting the culture of impunity in the region so the topic of assassinations and accountability would become subject to public discussions via research, exhibitions, film festivals, and a yearly award for the best text or film. Since Lokman's family announced the goals of the foundation at a touching ceremony of to celebrate his vivid life and mark forty days since his passing, as is the tradition; people have already begun to reach out. They have been contacted by several people offering to write about their experiences with political assassinations.

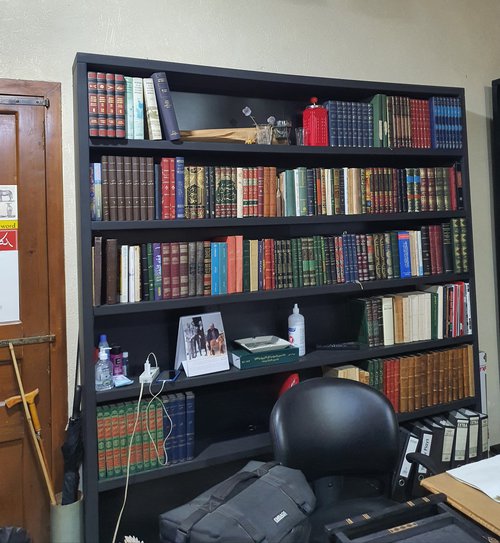

Four months after his death, Lokman's office stands empty. Photo by Sawssan Abou-Zahr.

The work begins

As Monika envisions it, the foundation would be an umbrella for peacebuilders and human rights defenders interested in the topic. The work span covers the present and the past, in the hope of "uniting the families of victims of previous political assassinations". It is an unprecedented step. The families usually come together on occasions of solidarity but have never acted collectively for their case, unlike the relatives of the forcibly disappeared and more recently the victims of the devastating Beirut explosion. In fact, the families of the disappeared are an impressive example on what long painful years of advocacy and perseverance can achieve. A commission for the missing and forcibly disappeared was finally established in 2020.

Accountability is the joint target for relatives of victims of political assassinations, forced disappearances and the Beirut blast. Therefore, Monika wants the foundation to "be the point where they can unite".

As I read Mekbel's statement that "we cannot say that someone was unjustly assassinated. We have no right to declare there are just deaths and unjust deaths", I can almost hear Lokman saying: "Work hard my friends, you have a lot to do with the foundation".