Sima Atri and Salvator Cusimano are entering their fourth and final year at the University of Toronto, Canada. They travelled to Uganda for three months to conduct research focusing on the place of youth in conflict, peace, justice, and reconciliation.These are some of their insights on field research from their experience.

We travelled to Uganda from the beginning of May to early August 2011. We had spent months conducting research at the University of Toronto into issues surrounding youth affected by the recent war in Northern Uganda between the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the Government of Uganda. In Uganda we hoped to collect quantitative and qualitative data in the field to test the assumptions of existing research and provide answers as well.

However, research abroad can be difficult, especially if you’ve never traveled to the country before and have limited field research experience. We were wondering how would we connect with people on the ground? How would we be received by the local population? Most importantly, how would we know if we made a meaningful contribution with our work and not just add to the plethora of foreigners who are just there?

Before you go

Do a lot of research and think critically: what questions do you have? How would you answer them? Remember that hundreds of people have done research in Uganda - try to figure out what they have missed, what they did wrong, or how you could do it better. It is also helpful to share your ideas with other researchers or practitioners who have spent a significant amount of time in the country.

Ask yourself a series of related questions before moving ahead with your project. How will your research benefit people in the short and long-term? What will your research add to the existing body of knowledge? Perhaps most importantly - who are you doing this research for and what are your motivations. If you're not thinking about the needs and desires of the people who participate in your research, you probably won't produce anything that's of much use to anybody and you may risk rejection by Ugandans themselves - they've encountered many researchers and they can distinguish between the serious ones and the insensitive ones.

Prepare yourself mentally, emotionally, and physically. There are many of the comforts of home in Uganda, but getting there and staying there is tough.

Reserve at least 3 months to do your work, especially if it's your first time going to Uganda. You might want to give yourself even a little more time to take a break for instance in the middle and at the end of your trip to travel around this amazing part of the world.

When you arrive...

- Take a few days to get used to life. Find a comfortable place to stay, check out the local food, and get a sense of how life flows.

- Try to meet as many people as you can and form a good network on the ground, especially with individuals who have connections with locals and will be committed to your project.

- Check if your research question remains as valuable as you have thought. Test your assumptions by talking to as many people as you can. Your contacts are certainly useful but also engage with other people like those staying at your hotel, the guy next to you at the bar, or the lady serving you food at the restaurant. They all have important, enlightening opinions and experiences; just take care not to pose deeply personal questions to complete strangers. Don't embarrass yourself by sticking to a research project that made sense based on your reading – adopt it to the realities on the ground and the perspectives of the locals. Avoid bringing copies of your surveys from home because you probably will have to make changes to your survey or interview questions. There are plenty of cheap photocopy and printing shops and reliable wireless internet in some places.

- Always be vigilant about the intentions of the people you’re dealing with. Try to get a good sense of local price levels. Conducting research costs money, but not the extravagant amount that some locals will quote to take advantage of you, the foreigner. There are certain buzzwords in Uganda that you should learn very quickly. You will be asked to pay for 'mobilization' (gathering participants), 'facilitation' (introducing you to the community and its leaders, translating, and collecting the data) and 'refreshments' (soda for everyone!). These fees are always negotiable, depending on the qualifications of the individuals and the time commitment required. Relatively fixed costs include transportation, photocopying and printing, writing materials, and mobile phone airtime (but don’t be afraid to bargain for these either). While traveling with NGOs, you may be asked to pay for fuel. These big-cost items provide opportunities for people to take advantage of you. It’s especially easy when sums like $50 sound little to you, but are actually astronomical in local terms.

- You need to consider where you will live. If you are mostly working in one place, then you should think about renting an apartment. However if you are traveling, your only choice is to stay in a guest house. Guest houses (even the cheapest) will almost always be more expensive than renting so if you are on a tight budget, this is something you should keep in mind. The cheapest guest houses in 2011 were around $5 per night usually with breakfast included, but most people that we met were paying around $10-$20 per night for clean and secure accommodations.

- You have to figure out local eating habits and traditions. Chances are quite high that the busiest local restaurant is the best one in terms of both quality and cleanliness. In the bigger towns and cities, you can find ethnic food (especially Indian and “Western”). Before you leave, some people may tell you it is never safe to eat something from the street. However, we loved the street food! Just pay attention to the way the food is being cooked and is served to you.

- It is crucial to be aware of the way you dress. It is helpful to try to find out how locals dress before you travel. For women, shorts and short skirts are very inappropriate in Uganda. Showing your legs is more taboo than tight or low shirts. Either way, to prevent name-calling and to gain respect, you should avoid wearing tight clothes. Even men are ill-advised to wear anything other than a decent pair of khaki pants. Jeans and shorts stand out not in a good way. Ugandans care a lot about shoes; try to keep yours clean (as difficult as this is).

- Technology is very important for conducting research and living in Uganda. Bring a computer with long battery life because frequent and potentially long power outages, especially in the North, can occur. Bring a camera, but realize that although Ugandans generally enjoy having their photo taken, you should always ask permission first. Finally, having a local cell phone is essential. Ugandans all over the country have them. You can buy a good cell phone for about $15 in any town. You should get one that is unlocked so that you can switch companies as they’ll offer different promotions over the course of your stay that will save you a lot of money. Ugandans do not really send text messages, and very few have email access. It is also considered polite to call someone rather than have them to call you (partly because receiving a call is free, but making one costs money).

- We would sometimes bring small gifts for the community’s children to keep them busy while we did research with the adults. However, be aware that giving candy or pencils to a group of three children could quickly attract hundreds of children that live in any given village, and you will be expected to provide something to every child. Think carefully about the way that giving children these things in full view reinforces the expectation that foreigners will simply give handouts. This can undermine not only your own research efforts, but the efforts of foreigners who come after you leave.

- Learn how far away a particular village is and get numerous ideas on transport costs before you negotiate with someone. If you are aware of the price for locals you can (and should) bargain yourself to obtain that same price. Mentioning the prices of competitors (or bargaining in the presence of competitors) always helps.

- Learn monetary norms. You should be aware of how much other researchers with similar planned activities are paying, as well as how much NGOs generally charge for their services.

- Don't get discouraged! You'll run into a few bumps on the road but don’t lose your confidence and persistence.

Getting to the field

Safety should be your number one concern. The major form of transportation in Uganda is 'Boda Boda' (motorbike), which we used a lot because of its convenience and relative affordability. However, we do not recommend it. If you can find other means, go for it. One of our friends was involved in a serious Boda Boda accident and we, personally, witnessed many others. You can possibly travel with NGO workers in their vehicle, but also find safer (but still iffy) forms of transport like coach buses, taxis ('matatus' or minibuses) or shared vehicles. You can also simply hire your own driver for your stay. Despite the dangers of traveling on 'Boda Boda', it came to be beneficial though: our bored Boda-men were often more than happy to help us with translation and community relations when we arrived. We also suspect that traveling like the locals presented us as unpretentious youngsters who enjoyed connecting with villagers in a familiar way. On the contrary, the big, white SUVs and Range Rovers that many researchers and aid workers travel in even intimidated us (this is speculation though).

In order to decrease the potentially occurring amount of disruption of your research, it is better to pair up research with a program or meeting for which community members will already be gathered, especially if the subject of the meeting is relevant to your research. For example, one of our most successful field trips was organised to precede a community dialogue session on conflict in the community. Pairing up the research with an already existing program can also mitigate the troublesome expectations of significant compensation from researchers. If there are no NGOs working on programs relevant to your research questions, you could choose to offer a training yourself before or after you conduct the research.

Collecting the data

Once you gain access to the community, you must still convince them that their participation is worth their time. This is not simply to ensure that you are received kindly in the community: if the community does not understand why your research is important to them, you may end up without good data. The average Ugandan has likely participated in some sort of research project like yours and will be skeptical that you are any different than the last person who came. Furthermore, they are giving up their own time to spend with you. Therefore, you might offer them compensation. However, you’ll collect the best data if the community feels that they have a stake in taking the time to think carefully about their responses, in providing honest information, and trust you to be their voice to the outside world.

Organisation is essential. A data collection session with dozens of people present can quickly spiral out of control. Devise a strategy for not only collecting the data in an orderly fashion, but also for managing questions people may have in the process, for incorporating latecomers, and for keeping track of participants.

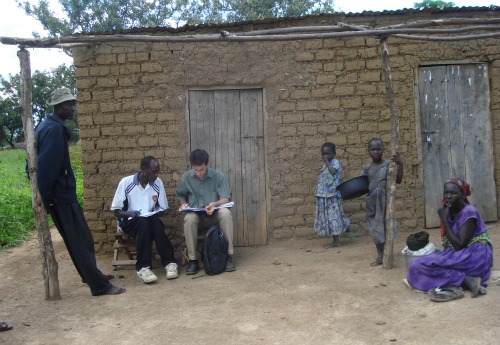

The means of collecting data will depend on the format of your questions. Ourselves, we did key informant interviews and short questionnaires. We preferred interviewing people from the community before and only asked them to fill out the questionnaire afterwards. If you’ll be using a survey, it is vital you translate it into each local language. According to our experience, the best people to translate were the staff at cultural centers. A high-quality translation of our 25-question survey cost $10 (but you might be prepared to pay more).

We divided the group into those who could write and those who were illiterate. This task required tact and sensitivity. Keep in mind that in Uganda, women are generally much less-educated than men; the group division can therefore produce an uncomfortable gender divide. Try to provide as much support as you can without singling them out as “illiterate.” Many illiterate people will attempt to fill out written materials out of embarrassment at their abilities. It is your job as a leader and facilitator to keep an eye out and assist those in need quickly and without causing commotion. We had a facilitator to read each question in the local language to the group which is able to write. Subsequently, community members would individually answer their own survey sheet. Otherwise we did the survey orally with each person. Always remember to bring pens and buy them in bulks because they often get taken.

The final, very important issue, is the question of compensating participants. We had a very hard time deciding what was right to do. In Uganda, it is even more difficult because there certain norms accompany public meetings. Any time an NGO or government official gathers people, even if it is a workshop specifically intended to help the community, they will provide one bottle of pop, a snack, and often cover the travel costs associated with attending the meeting. Although these are good gestures, community members now expect them and nothing less. Otherwise people often become frustrated and annoyed, even if their participation could have a direct impact upon their community. Before you decide whether to compensate and how to do so, consider potential ethical implications. On the one hand, an attitude of dependency intensifies that has begun to hinder progress in Uganda. In fact, instead of appreciating the actual value of the research, attendees become more concerned with what they receive than what they can contribute. On the other hand, you’re taking up people’s time and therefore they deserve something that is equal in value to their time.

In general, we suggest to compensate participants since your research will likely not bring them any concrete benefit in the short-term that would offset the time they have sacrificed to join. It does not mean, however, that you have to perpetuate the troublesome cycle of dependency. There are ways to contribute sustainably to a community. One novel approach taken by some American researchers was to give young participants a package of school materials. One of our preferred ways was to give donations to village savings association if they existed (these are very common, and a little bit of money goes a very long way and is generally more sustainable than a handout to individuals). This approach cannot only improve people’s lives but also create positive associations between research and sustainable development.

Living arrangements in Uganda

Before you go home

There are two things you should make sure to do before you go home. First, take the time to travel and explore the country. It is not only a great opportunity but will also help to put your research into a cultural, historical, and political perspective. Second, make sure to collect emails and phone numbers from everyone you spoke with. You will need them for citation purposes, to send the final product and to potentially ask for feedback before the research is published.

After you go home

Follow through with your promises to send your research to those who helped you. This is simply the right thing to do. It will help NGOs on the ground to have a better picture of the communities they work in, and if it reaches the community they will be very glad to see that something came out of the time they gave up to join you. If you can, try to get a summary of your research translated into the local languages so that it is accessible to the community members you interacted with.