Local organisations are challenging negative stereotyping of Kyrgyzstan’s many minority groups – which has led to violence in the past. Image credit: Robert Saltori.

Local organisations are challenging negative stereotyping of Kyrgyzstan’s many minority groups – which has led to violence in the past. Image credit: Robert Saltori.Despite some decline in nationalist rhetoric in media, our experts indicate the growing number of groups which are potential targets of hate speech and victims of hate speech crimes. Media sphere analysis for the last year has shown that, in addition to ethnic groups, the main targets of hate speech in Kyrgyzstan are religious and LGBT groups.

Last year the abusive attacks in media were mainly against ethnic groups. They were especially strong in 2010, when southern Kyrgyzstan faced ethnic violence between the Kyrgyz and Uzbeks that resulted in hundreds of dead and thousands of wounded. Back then, media and journalists were accused of inappropriate coverage of the issues and incitement of ethnic conflict.

Society has an opinion of the unrestrained freedom of expression which often leads to the transmission of violent statements in public discourse. Some journalists and speakers don’t understand the difference between freedom of expression and hate speech, and use stereotypes, clichés, ad hominem attack and dehumanising metaphors against minorities.

One of the reasons could be that Kyrgyzstan and its media sphere are the most free in Central Asia and outrank many states of the former Soviet Union. According to the World Press Freedom Index 2016, provided by Reporters Without Borders, an international journalistic organisation, the country ranks rather high.

Image credit: Inga Sikorskaya.

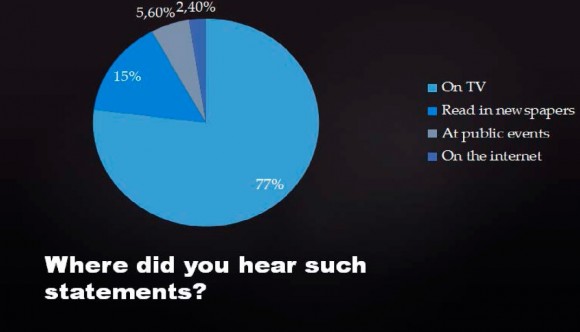

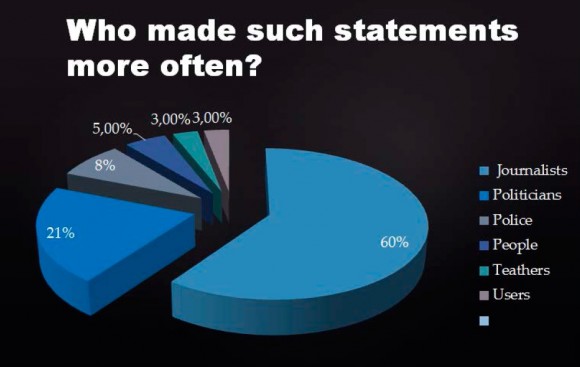

Image credit: Inga Sikorskaya. (Above and top). “People’s attitude towards hate speech” - analysis of hate speech in print, online and broadcast media in Kyrgyzstan by the School of Peacemaking. Image credit: Inga Sikorskaya.

(Above and top). “People’s attitude towards hate speech” - analysis of hate speech in print, online and broadcast media in Kyrgyzstan by the School of Peacemaking. Image credit: Inga Sikorskaya.Peaceful initiatives to prevent hate speech

Founded in 2010, the School of Peacemaking and Media Technology is the only organisation in Kyrgyzstan and Central Asia that started combating the spread of hate speech in media and on the internet.

Based on local experience and international cases, it has developed its programmes to reduce the potential for renewed ethnic conflict in the Kyrgyz Republic. As part of its work, regular media monitoring for hate speech has been established to study public opinion, and based on its results, innovative training materials are developed for journalists, editors, and activists to train them on how to overcome hate speech.

Approaches implemented by partner media NGOs in the Balkans and Southern Caucasus have been used to prepare workshops. For example, training reporters in Team Reporting, their joint work in multinational journalist teams for unbiased reporting have become a preventive measure to reduce tensions in the society. Specific discussions on removing stereotypes in reporting and among public speakers from conflict zones have been developed and organised to make them tolerant in their statements.

Challenging stereotypes

"After the training, we found it easy to work with material relevant to ethnic issues because we have the necessary skills and techniques to interact with ethnic groups," Ernist Nurmatov, editor-in-chief of Format.kg web portal based in Osh, said.

The Encouraging Diversity Through Media Program launched in 2014 helped journalists cover ethnic, linguistic and cultural diversity, overcome hate speech and develop a large online course, Diversity Reporting, which now covers 145 students.

Media monitoring also makes it possible to react quickly and unambiguously to manifestations of hatred and hate speech in statements made by public officials, and consistently document such actions.

"Hate speech studies have become a tool to protect the rights of minorities through monitoring and recording of hate speech incidents," Alina Amilaeva, regional assistant to anti-hate speech projects of School of Peacemaking, emphasised.

"Also we help local NGOs not only in Kyrgyzstan, but also in Central Asia, analyse rhetoric and its consequences upon request in order to settle conflicts between the perpetrators and victims of hate speech. Besides, we started covering issues relevant to religion and faith, which are sensitive now, and explaining to the media how not to stir up hostility."

The involvement of stakeholders into the combat against hate speech is another approach.

For field surveys and studies of hate speech impact on the society, the School of Peacemaking involves the staff of related NGOs that work on the issues of minorities. Some of them were the victims of hate speech from xenophobic groups. These help to generalise the findings in a more competent way and provide their own recommendations.

Activists say this approach is important. "As to the practical outcomes of these surveys, human rights defenders and activists use them in their work for better advocacy around vulnerable minorities by referring to the study that proves the use of hate speech against these groups," Alia Moldalieva, media coordinator of the Coalition for Justice and Non-Discrimination (Bishkek), said.