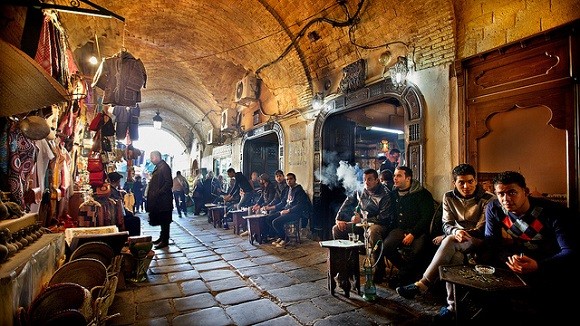

The Medina in the Tunisian capital, Tunis. Image credit: Michael Foley.

The Medina in the Tunisian capital, Tunis. Image credit: Michael Foley.These meticulously hand-crafted silver pieces contain an unusual mix of symbols: Christian fishes, Jewish stars, Muslim crescents, hands of Fatima, birds, and olive trees. Nasser, one of the five Ben Ghorbal brothers who own the shop, explained to me that the symbolism is universal.

“The three elements of life are air, the sea, and the earth… they are the only things that are concrete, true, and sure.” While the fish may be associated with Christianity, it is also a symbol of the sea, just as the crescent represents the air and sky, and the floral motifs that set the backdrop for most of the pieces in the shop evoke the element of earth.

Emphasising the humanist message of tolerance that he strives to convey in his jewellery, Nasser continued, “In Tunisia, there are Muslims, Christians, Jews. We don’t make a product that is unique to one religion or the other. We make something that everyone can wear. I believe that a person must make his life beneficial to others; he has to give satisfaction to everyone.”

Tunisia: a model of interfaith harmony?

This aesthetic style and technique of jewellery-making, called nemli, was developed by Mouchi Nemli, a Jewish man from Djerba, in the 19th century. Djerba, a small island off the eastern coast of Tunisia, is home to the Ghriba Synagogue - the oldest in Africa - and has long been considered a model of interfaith coexistence.

It is also the ancestral home of the Muslim Ben Ghorbal brothers. In 1910, the family relocated to Tunis, and in the 1970s, Nasser’s father decided to re-imagine the traditional Djerban jewellery craft, adapting the style and size of the pieces to a modern audience while retaining the artisanal technique and symbolic motifs. Now, almost 50 years later, the business is being passed along to the third generation of artisans as Nasser trains his son Mohamed. And this summer, the business welcomed another new apprentice: Antonia, a Christian woman from Spain.

Antonia was attracted by the hand-crafted style of the jewellery and the message of tolerance behind it. “Everything is mechanised now,” Nasser lamented. “So, she liked the charm and creativity of the hand craft - the patience it requires. She asked to learn. She said to me, ‘For me, the essential is that I get to know people and that I am able to communicate with them [through the art]. Relationships last forever.’” After training his apprentice for three months, Nasser said, “Now it’s like she has a family in Tunis - with us - and now I have a family in Spain.”

The essential concern - humanity

Since the 2011 revolution that deposed dictator Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali and catalysed the Arab Spring, Tunisia has suffered from mounting terrorist activity during its political transition to democracy. The Bardo Museum and Sousse shootings in March and June this year resulted in a total of 59 fatalities, who were mainly foreign tourists. When I asked Nasser if he was worried about the potential implications of this situation on his own business and safety, he responded, “They want to make us afraid, but we cannot fall into their trap. Tunisians are warm, tolerant, and welcoming. You can find everything here [in Tunisian history]: Carthaginians, Arabs, Romans, Berbers, Ottomans, Jews, Christians, Muslims, the French, now Americans and Germans... It’s always been like that. Two days ago there was a party in the streets of Sousse to show solidarity. That’s how we should be reacting.”

He continued to tell me that he believes that his jewellery can have a positive effect, no matter how small, on peacebuilding in Tunisia. “We try to reach as many people as possible, and then they reach as many people as they can. We are not alone in the world.”