There are numerous places of historical conflict around the world where there is a clear need for helping those involved to find common ground.

The current events in the Middle East and North Africa, in which popular uprisings are toppling, or at least trying to topple, long-standing regimes, are welcome. Yet there are no guarantees that a seamless shift to democracy will inexorably follow. Sadly, there is a real risk that new inter-community disputes will arise in those areas in the months and years ahead.

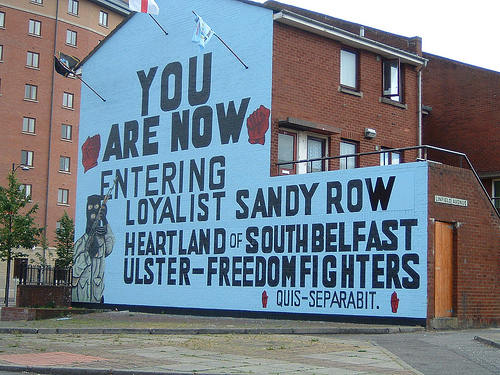

My experience as a minister involved in the successful peace process in Northern Ireland has led me to two conclusions. First, there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to what are, in effect, difficult problems based on long-standing mistrust and deep-seated differences, which can be based on ethnic and territorial rivalry (eg Cyprus), religious divisions (eg Northern Ireland) or national aspirations (eg the Basque region).

Secondly, those working to bring about peace and reconciliation need to be able to identify the pre-conditions necessary in each case which would allow dialogue to commence, and also the principles on which peace processes can be developed.

Without pre-conditions, there will not in many cases be enough common ground to enable progress to get underway.

Crucially, there has to be a clear recognition on both sides of the conflict that the status quo is not a tenable option. Usually this occurs, as in Northern Ireland, when the respective communities and the combatants have reached a point at which the prospect of continued conflict is too distressing and exhausting to contemplate.An important way of identifying what preconditions have to be met on both sides, is to set up back-channels as a means of informally but authoritatively scoping out the barriers to immediate progress. This was hugely important in Northern Ireland for both John Major and Tony Blair. Of course, the most important precondition was that of a ceasefire.

It is important to establish as soon as possible some common principles. The first and most important is parity of esteem. That is to say that each side has to recognise that their opponents have a legitimate stake and equal status in the process.

Secondly, there is an important place for confidence-building measures. These can prove to be very difficult barriers in many ways. In Northern Ireland for the Unionist community, it was understandably important that the IRA engage in a process of decommissioning their weapons. However, for Republicans this proved to be very difficult to deliver, because it could easily be held to be a symbol of defeat and, in consequence, could be portrayed as showing disrespect to those who had been engaged in the previous armed conflict.

Ultimately, the key to unlocking the path to peace in Northern Ireland, in the form of the Good Friday agreement, was in finding a political settlement which would enable both sides to retain some dignity and distinct political identity.The devolved institutions in Northern Ireland, which managed – just – to bring all of the main strands of political identity into an agreement were at the core of the process. This was constructively ambiguous, in that it left Nationalists and Republicans the space to accept a settlement short of full unification with the Republic of Ireland, on the basis that they were able to retain the aspiration as attainable but only with public consent.

Similarly, for Unionists, and Loyalists, Northern Ireland remained within the UK, without the ongoing trauma of violent terrorism.

Other aspects of the process were both painful to contemplate for some sections of the community and, at the same time, raised question marks with right-thinking people about the rule of law and the independence of the criminal justice system. The most obvious manifestation was the prisoner release scheme, which in some cases led to the release under licence of terrorists who had been convicted of appalling atrocities. Although I would argue that this was necessary, in terms of the greater good, it was a scheme with which very few people felt comfortable, myself included.

One final point, tangential to the peace process in Northern Ireland, but which I feel is important in such circumstances, is that of personal identity.

Being a terrorist – having aims and values outside of the mainstream of society and the state and being prepared to use extreme violence and criminality to pursue them – confers a distinctive identity, a purpose in life and a broader connection of solidarity with comrades in arms. The paramilitary apparatus and ethic involved is not coincidental; it serves to foster a sense of being a disciplined, interdependent fighting force.

In many ways, the persistence of dissident groups such as the ‘Real’ IRA, serve as an illustration of this phenomenon. Although rejectionist, in the sense of not buying into the peace process, they also provide a home for those who cannot psychologically adjust from that outsider status to becoming part of a political settlement based on constructive ambiguity. Similar situations will undoubtedly arise in other peace processes.

The important thing to bear in mind is that there is no single blueprint. However, with the best possible and achievable preconditions (hopefully as few as possible) and the right principles – difficult though they may seem at the time – it is possible to achieve lasting peace.