Peace Direct is pleased to expand Insight on Conflict's reporting on peace and security issues around the world. Our network of Local Peacebuilding Experts have considered key data on recent events in their region, and analysed the impact for peacebuilding.

This month, we have selected four countries that have seen a recent rise in levels of conflict to analyse. Click on the links below to read the views of our Local Peacebuilding Experts in the following areas:

- Central African Republic - Martine Ekomo Kessy-Soignet

- Nigeria - Michael Olufemi Sodipo

- Yemen - Yemeni Local Peacebuilding Expert

- Pakistan - Zahid Shahab Ahmed

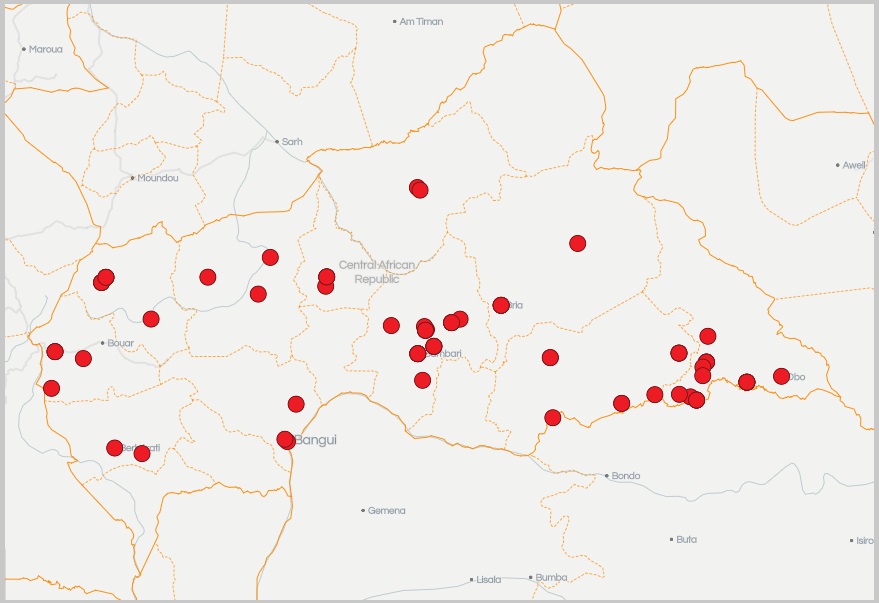

Central African Republic

The Front Populaire pour la Renaissance de Centrafrique (FPRC) and the Mouvement Patriotique pour la Centrafrique (MPC), two ex-Seleka armed groups, signed a coalition in November 2016 with their former enemy, the anti-Balaka. They agreed to attack another armed group, the Union pour la Paix en Centrafrique (UPC), led by the militiaman Ali Darassa Mahamant. Mahamant is also a former leader of the ex-Seleka.

Most of the fighting between these groups has taken place in the central Ouaka region, which has the country’s second largest city Bambari. Control of this region is of strategic importance, because of its wealth and location between the Muslim and Christian regions of the country.

Both the FPRC/MPC group and the UPC have maintained their military position on the ground and found reasons to discredit and attack their adversary. This situation has put significant pressure on all stakeholders in the crisis in CAR for several reasons:

- The divisions amongst the ex-Seleka show that there is a real tension within the group, mainly linked to personal interests of their leaders. The peacebuilding implication of this is that it will be necessary to deal with several armed groups who will develop on the ground. The difficulties will lie in identifying a clear chain of command and a leader able to speak on behalf of each of the groups. Negotiation and mediation are therefore challenging for both local peacebuilders, the government, and the UN mission, MINUSCA.

- The coalition between ex-Seleka and anti-Balaka group completely changes the way in which the conflict in CAR can be interpreted. It shows that both the anti-Balaka and some factions of the ex-Seleka who have been fighting each other are able to find common ground. This means that the narrative explaining the conflict in CAR as being intrinsically linked to communitarian issues does not make sense anymore in this area: the new coalition mixes two groups who attack and kill both Christians and Muslims.

This situation has negatively impacted civilians, who are the first and innocent victims of this settling of scores. However, despite these developments in the conflict in CAR, humanitarian and other work continues.

Implications for peacebuilders

The work of local peacebuilders in this situation will be vital. One group working in the area is Jeunesse Unies pour la Protection de l’Environnement et du Développement Communautaire (JUPEDEC).

JUPEDEC began working in Bambari before the UPC arrived. With some partner support they have provided care to vulnerable people, including internally displaced people originally from South Sudan, who have now fled to seek refuge in CAR. During this period of tension, JUPEDEC staff have provided food, water, sanitation and hygiene support, as well as first aid and medical help for children made orphans during the fighting, and victims of gender-based violence. They have also worked with the UN Office of Coordination for Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) and MINUSCA working with victims and IDPs.

The organisation used to work in areas controlled by the anti-Balaka during the day, and then slept in Bambari, controlled by the UPC, at night.

This situation was risky, because of the possibility of being suspected as traitors or intelligence agents for the anti-Balaka. So to avoid tension and attacks, JUPEDEC staff developed a strategy based on neutrality and inclusivity.

“By involving people from Bambari in our daily work, we were sure that the chance of one of them having family in the UPC was high. So we betted that the group would not disturb our humanitarian activity, because their family connections were working with us,” said a JUPEDEC staff based in Bambari.

Looking forward

While Mahamant and his men left Bambari a few months ago, they left behind a traumatised community, with rumours feeding fears of attacks on a daily basis. But although the data on the future of the crisis in CAR is not positive, the work of organisations such as JUPEDEC shows that there is always an opportunity to capitalise on developments to do some good. The communities local peacebuilders work in are effectively their family, and peacebuilders will always be by their side.

Martine Kessy Ekomo-Soignet is Peace Direct's Local Correspondent for Central African Republic.

For more information on the topics raised in this report, click on the following links:

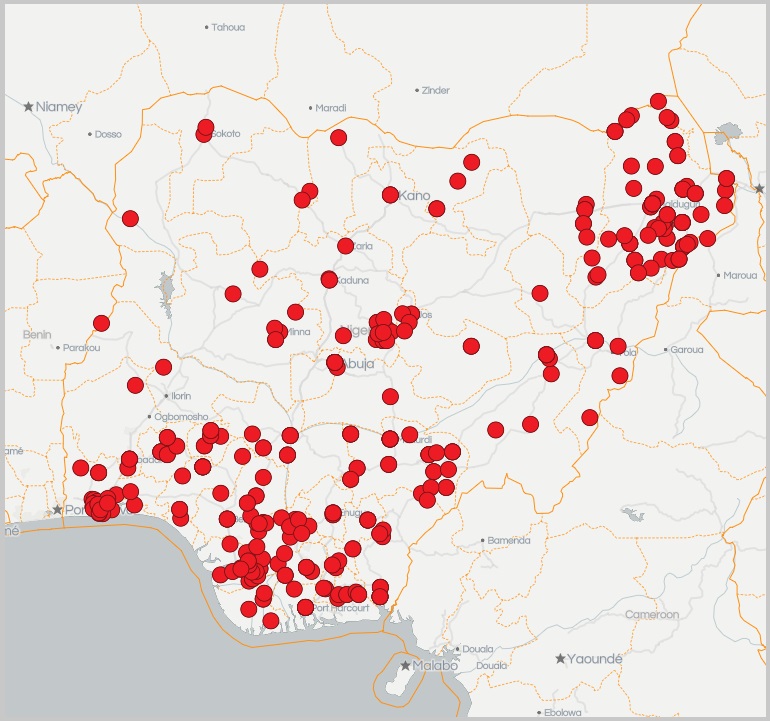

Nigeria

Security challenges include the insurgency in the north-east, agitation for resource control and militancy in the Niger Delta, activities of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) in the south-east, serial violence between herders and farmers in southern Kaduna and central Nigeria, sectarian and communal conflicts between the Yoruba and Hausa in Ile Ife, the proliferation of small arms and light weapons, and piracy in its national waters. These conflicts have led to the loss of life and property.

Crises between herders and farmers have been a major risk factor for mass atrocities in northern and central Nigerian states. For example, the security situation in southern Kaduna remains tense as a result of frequent attacks by herdsmen in the Kafanchan and Gododogo areas. In February 2017, dozens of villages were razed, scores of people killed and thousands were displaced from the latest attacks.

Meanwhile, counter-insurgency efforts by the Nigerian security agencies have resulted in the rescue of more children and women held in communities recaptured from Boko Haram, including some of the abducted Chibok schoolgirls.

Of the problems confronting IDPs, the fact they live in makeshift camps has made them more vulnerable to hunger, rape, suicide bombing and random attacks from Boko Haram. Their situation is becoming Africa's fastest-growing displacement and humanitarian crisis. There is a concern for the growing number of children being left out of school due to these conflicts, the displacement and proliferation of IDP camps, as well as the direct loss of life.

Inter-communal conflict: peacebuilding responses

In response to this insecurity and inter-communal conflicts, Nigerian civil society has organised key activities in recent months.

One example is the intervention of the Arewa Leaders (Northern Leaders) in the southern part of the country. The Arewa Leaders are community leaders of northern Nigerian extraction, who work on the clashes between farmers and Fulani, and have assisted in dousing the tensions between the two. The chairman of the Arewa Chiefs in southern Nigeria, Alhaji Haruna Katsina, met in January 2017 with the leadership of the Fulani Herdsmen. He pleaded with them on the need to respect their hosts in order for peace to reign.

The Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution (IPCR) and Global Rights also embarked on a dialogue, in March 2017, to find lasting solutions for the violent conflicts and bad relations in southern Kaduna. They frown at criminalising an ethnic group because of criminal elements among them, while encouraging civil behaviour and obedience to the laws of the land.

Stakeholders at the dialogue which took place at the IPCR in Abuja were of the opinion that solutions to the southern Kaduna conflicts could be replicated to help deal with conflict in Benue, Plateau and other states within the Benue-Niger gap.

My own organisation, the Peace Initiative Network (PIN), which is based in the northern city of Kano, uses sport as a platform to empower at-risk children and youths from diverse communities – indigenes and settlers, Muslims and Christians – with the peacebuilding tools to reduce their vulnerability to recruitment by violent extremist groups.

PIN runs peace education and sporting activities designed to help young people develop understanding of cultural and religious differences, as well as the ability to respect and sustain peace and community cohesion. PIN uses sport to help people understand and appreciate each other’s beliefs, values, and ways of life better, leading to a tolerant, harmonious and peaceful Nigeria.

These, and the examples above, illustrate how to make the challenge of creating ‘unity in diversity' meaningful and workable. Community institutions are well placed to take preventive action, and have the comparative advantage of their geographical proximity, as well as a better understanding of the cultural and social dynamics that give rise to group grievances.

Michael Olufemi Sodipo is Peace Direct's Local Correspondent for Nigeria.

For more information on the topics raised in this report, click on the following links:

Yemen

As previous updates on Yemen (see here, here and here) have indicated, the humanitarian situation in Yemen is dire. Any kind of progress in this context is difficult. Nonetheless, work to address some of the symptoms of this conflict is still taking place.

This month, the Yemen trends report discusses in depth one set of peacebuilding activities which has recently taken place. This workshop aimed to allow children to reflect on the terrible experiences they are undergoing in this conflict.

The Ebhar foundation for Childhood and Creativeness, along with the Basement Cultural Foundation, explored coexistence through innovative and creative lines, attempting to show the impact of the war on children.

They brought together students from 15 schools to talk about the war and the conflict in the country, under the supervision of sociologists and psychologists.

Then, for three days, they all sat together to draw their ideas and feelings with the help of young professional Yemeni artists.

The workshop, called “Green Ideas and Colourful World,” ended with an exhibition in the Basement Foundation Hall.

The results were beautiful, revealing the perspective of children on the war through their graphics and images.

“We wanted it to be smooth and healing, reflecting reality and hope,” said Ghada Al Haddad.

“Some have golden hopes and others were pessimistic. But they were all very brilliant and very creative, regardless of the gloomy colours and ideas,” she added.

Some of those who attended noted that it is difficult to portray the scenes of fear, death and panic under the bombardment. But it is a good tool for children to express their visions without fear and in a safe environment with professionals, they added.

Shaima Hashem, the chair of the Basement Foundation, said that the experience was shocking, with so many issues to address from the war.

One of the kids tried to describe his friend, who died under shelling, and another tried to depict the cholera situation around him, she said.

The suffering of the children was clearly there – but so were hopeful colours and the urgent need for peace. The final pictures were the innocent testimony of children in dark surroundings, Ghada added.

Beauty amidst the darkness

The consequences of the war in a country as poor as Yemen are high. The photos are full of hardship, including the malnutrition and epidemics that have killed many children. The kids live in an atmosphere of fear, of dying under the rubble. The fear of [being left with] serious disabilities is also there and reflected by the kids, according to Shaima. There is also frequent panic about the spread of disease.

The world media have not written thoroughly about what the kids in Yemen see and feel. But it can be seen clearly in the neurological clinics in Sana'a city. The scene and the portrait are very painful there, crowded with large numbers of children. Can you see it? Can you imagine it as those kids did?

At the workshop, the children painted from their own experience. Standing next to each other in the gallery, the children’s paintings were distinctive, telling the story of the collapse of their country through their experience and memories. The kids were not only telling their own stories, but also the stories of their families and friends.

After the kids’ gallery, a group of artists, academics and intellectuals who were interested in the topic came together. They discussed the impact art and reflection can have in peacebuilding.

The side activity also provided an opportunity for young people to discuss with the group. The panel explored the liberation of artistic forms from traditional lines, allowing young artists to express themselves and their surroundings widely and loudly.

The conflict in the country keeps escalating, with severe clashes on all active fronts. The current armed operation has fractured the economy as well as the remaining social fabric. The humanitarian situation has become catastrophic, always reaching new milestones: in the last year, the number of children killed has increased by 70 per cent. Thus, Yemen’s children have paid the highest price. According to Unicef, a child dies every ten minutes.

Amidst this chaos, the children’s bright and dark colours reflect both reality and expectations – their visions and aspirations. The portraits are a transparent testimony to the world through the eyes of innocents, sending a message that they cannot tolerate what is happening, that despite their pain, they are dreaming for peace.

Information on local peacebuilding in Yemen is provided by Peace Direct's Local Peacebuilding Expert, who wishes to remain anonymous.

For more information on the topics raised in this report, click on the following links:

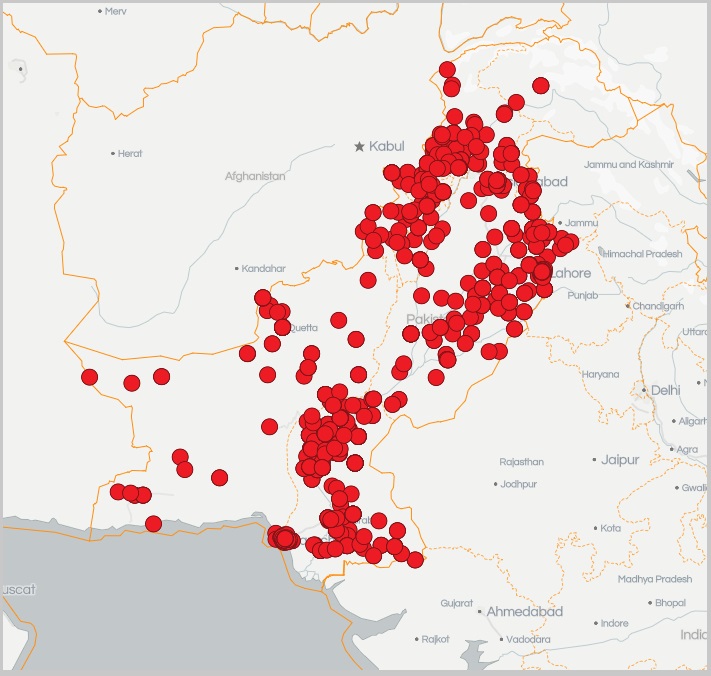

Pakistan

In February 2017, an attack on the Sufi shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, in Sehwan Sharif, Sindh, provided a stark reminder of the extremist threat to Sufism. ISIS has claimed responsibility for the attack, which killed 75 and injured 200 people.

Sidra Rafique has been involved in CVE work for several years. She viewed the shrine attack as an attack on the peace loving people of Pakistan. “Sufi Islam not only preaches love, but also practices a message of spiritual devotion and love for all regardless of their creed, caste, gender or religion,” she says.

Sufism has a strong following in Pakistan, but religious fundamentalists and extremists, especially the ones influenced by Wahhabism, perceive it as un-Islamic. This widespread perception is a major cause of attacks on Sufi shrines in Pakistan.

The government response

In response to the February attack, Pakistan’s armed forces launched Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad. This is similar to Operation Zarb-e-Azb, which was initiated after the terrorist attack on the Army public school in Peshawar, in 2014.

The new operation specifically targets the Jamaat-ul-Ahrar, TTP, and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi terror groups – supporters of ISIS in Pakistan. In the first week of its launch, Radd-ul-Fasaad led to the killing of over 100 militants across the country.

While the government measures its success against terrorism through the decrease in number of terrorism-related casualties, it is important to underline that its National Action Plan (NAP) on terrorism has been largely ineffective in countering the influence of home-grown extremist organisations. This is a reason for which many local scholars claim that intolerance and extremism are on the rise – something that deserves greater attention from the government in relation to countering violent extremism (CVE).

Perspectives from Pakistan

The international community has focused on CVE since the start of the ‘War on Terror’ in 2001. This shift in policy at global levels has led to an increasing focus on peace education interventions in Pakistani madaris (Islamic seminaries). But there is ongoing controversy in Pakistan over when and how to engage with former members of extremism and militant organisations.

While most of the attention of CVE and peacebuilding programmes has been focused on the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa area, it is important to note that violent extremism is a serious problem in many parts of the country.

According to a Pakistani peace scholar, Dr Saeed Ahmed Rid, “the attack on Sehwan Sharif is another proof of the fact that extremism and terrorism are now rising in rural Sindh.”

A Sindh-based peace activist, Sanam Noor, blamed the February attack on the “non-serious attitude of security agencies of the country.”

Noor’s point is valid because the phenomenon of threats to Sufi shrines is not new, and the government could have provided better security, especially at the time of ceremonies like Urs.

Raheel Sharoon of the Diocese of Raiwind - Church of Pakistan has been engaged in interfaith dialogues for many years. He shared feelings of sadness at the Sehwan Sharif attack: “I was not shocked. There has been feeding and nurturing of this of hatred and violence in the name of religion to our populace for almost 35 years. So when we experience this hatred in action, unfortunately it does not ‘shock and awe’ me anymore.”

Another scholar, Abdul Basit said that “Not just the Sehwan Sharif attack, but the assault on Maulana Abdul Ghafood Haideri in Mastung, as well as the attack on Shah Hurani shrine in Khuzdar, clearly indicate that the extremist worldview of ISIS not only ex-communicates Shias, but also apostatises other Sunni groups, which do not subscribe to its extremist ideology.”

Basit added that the Islamic State is deliberately hitting the sectarian and communal fault-lines in Pakistan, which will negatively affect the ongoing CVE efforts. Since its creation, Pakistan has been a divided society, based on ethnic, religious, and sectarian lines, and these dynamics help internal and external terrorist factions operating here. The divisions create challenges for peacebuilding work, which has become more difficult with the increasing presence of ISIS. But this also provides peacebuilders with the opportunity to address such social divisions.

Countering violent extremism

The government and its local and international partners need to devote greater attention to improving the National Action Plan. There need to be more discussions on the scope of the policy and its implementation across the country. The policy should move beyond CVE to preventing violent extremism (PVE), which is as important as having a long-term plan on CVE. Structural issues, such as social divisions based on ethnic, sectarian, and religious lines, need to be addressed to prevent violent extremism.

In this context, it is vital to deal with confusion relating to sectarian organisations, especially the ones that promote violent extremism, by treating them as terrorist groups. The government’s confusion in this matter acts as an encouraging factor for groups promoting violent religious extremism.

It is also important that peacebuilding organisations working on addressing social divisions, such as through inter- and intra-faith (Shia-Sunni) dialogue, also engage Sufis and their devotees in peacebuilding processes. Sufis have a large following in Pakistan and their involvement in peacebuilding activities could strengthen CVE/PVE efforts.

Above all, the relevant government authorities must work side-by-side with civil society groups, local, and international NGOs, to develop a comprehensive plan on CVE/PVE.

Zahid Shahab Ahmed is Peace Direct's Pakistan Local Peacebuilding Expert.

For more information on the topics raised in this report, click on the following links:

This Peace and Conflict Report is published by Peace Direct to highlight local peacebuilding initiatives in conflict zones. Please note that the views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of Peace Direct.