Restorative justice: A thread repairing the fabric of peaceful societies

Oshan Gunathilake explores restorative justice in peacebuilding as a community-centric alternative to punitive justice systems.

When I’m asked to define what ‘restorative justice’ means to me, I always face a dilemma with terminology. In my view, it goes beyond the prevailing narrative of ‘justice’, which revolves around determining who was ‘right’ and who was ‘wrong’ and inflicting punishments, such as exclusion from society, reparations, or physical pain. Under this retributive lens, understanding the needs or interests of the people who break these pre-established rules is very often overlooked. In this way, we have made it a norm to see social harm be addressed with more harm – and somehow, we expect that to bring healing and peace!

Restorative justice instead prioritises healing, righting wrongs and strengthening relationships among individuals who are in conflict, as well as the communities around them.[1]

Its primary goal is to restore peace through intentional action, acknowledging harm, accountability and prevention of future harm.

A victim-centred approach

At its heart, restorative justice requires both parties working together to better understand each other’s needs and motivations in order to repair their relationship, find forgiveness, heal the harm done and find a peaceful resolution. This does not mean that perpetrators are absolved with a pardon.

The restorative lens also requires the wider community, who are indirectly impacted by the harm, to come together and offer support for this healing journey while ensuring the underlying needs/grievances that caused such harm are minimised. Likewise, communities engaged in the process learn to replace punishment with healing, hatred with forgiveness. This allows the space required to overcome shame, intimidation and judgement for both victim and offender, while facilitating the restoration of harmed relationships.

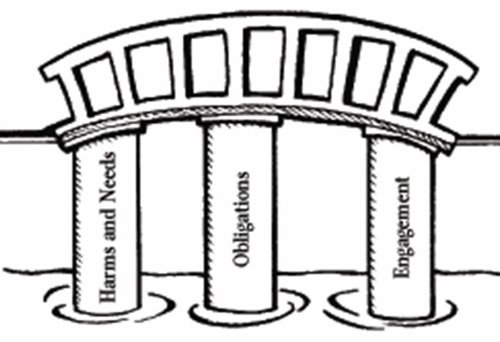

As such, the core pillars of restorative justice lie in: recognising the connection between addressing harms and fulfilling individual and community needs; a commitment to healing; and dedication to rebuilding the broken fabric of society.

Howard, Z. 2002. The Little Book of Restorative Justice. PA: Good Books.

Some of the core aspects of restorative justice originate from restorative practices in Indigenous cultures, including the emphasis on community wisdom, equality, and respect for all members. In some Indigenous societies, harm to an individual affects the entire community, leading them to support both the victim and perpetrator in seeking forgiveness and healing. For example, in Maori culture, the interconnectedness of everyone is valued, and traditional “Maraes” serve as sacred spaces for victim-perpetrator forums, addressing harms, root causes, and the healing needs of all. In Maori tradition, priority is given to addressing harms and needs, offender obligations, and community engagement, rather than solely focusing on assigning blame and punishment.

Such practices are being adapted to address current harms in other societies. For example, the Restorative Conferencing Initiative is using restorative justice principles to address youth conflicts in Victoria, Australia. Through the Youth Justice Group Conferencing Programme[2], young offenders aged 10-18 participate in a series of youth justice conferences to support their healing and rehabilitation process, giving them time to reflect, strengthen relationships and work with their community.

According to the Restorative Conferencing Initiative, “It is a problem-solving approach that aims to balance the needs of young people, victims and the community by encouraging dialogue between individuals who have offended and their victims”.

The programme assesses their engagement, respect towards obligations, and understanding of the harms and needs. In this way, it fosters a participatory approach that aligns with restorative justice principles, and it supports juvenile perpetrators to transform their behaviour and contribute to peace.

A peacebuilding circle conducted by the author at the University for Peace (UPEACE) in Costa Rica. The dialogue was a part of our Film-based Dialogue series conducted in collaboration with SIMA Academy. The session began with a social impact film, followed a peacebuilding circle structure as explained in the article which further encouraged and empowered students to speak, in a safe space, on the injustices and harms they experience in the university community and seek solutions. Image provided by the author, with consent from participants.

Success rates

- A 2006 meta-analysis by Bonta et al found that restorative justice programmes were more effective than traditional criminal justice approaches at reducing recidivism.

- A 2010 study by the Center for Restorative Justice and Mediation found that victims who participated in restorative justice programmes were more satisfied with the outcome of their case than victims who did not participate.

- A 2012 study by the University of Minnesota found that offenders who participated in restorative justice programmes were more likely to complete their restitution orders than offenders who did not participate.

Satisfaction rates

- A 2004 study by the National Institute of Justice found that victims who participated in restorative justice programmes were more satisfied with the process than victims who did not participate.

- A 2008 study by the University of Pennsylvania found that offenders who participated in restorative justice programmes were more satisfied with the process than offenders who did not participate.

- A 2011 study by the University of British Columbia found that community members who participated in restorative justice programmes were more satisfied with the process than community members who did not participate.

Using restorative justice in peacebuilding

Restorative justice can strengthen peacebuilding efforts in conflict-affected communities by helping to address harms through relationship building, reconciliation and healing. In such settings, criminal justice or retributive justice alone may not restore the torn fabric of the community.

I personally observed the power of dialogue as a form of restorative justice and peacebuilding at the University for Peace in Costa Rica. We supported a highly diverse student body – representing over 40 countries – to initiate dialogues to address disagreements over matters of public spaces, shared values and other principles and beliefs based on their background and intersecting identities.

The students created a space for dialogue, reflection and reintegration, by organising a film screening followed by a peace dialogue. They used an approach developed by Kay Pranis for ‘Peace Circles’[3], inspired by the Native American traditions, which focuses on community discussions around harms done, the needs of victims and the obligations of offenders.

This dialogue strengthened the communal bonds between students. They were more understanding of each other’s needs and values, and openly started to discuss their differences, emotions and difficult subjects in the safe space they created. In turn, they found it easier to find consensus on many things, in recognition of their shared humanity.

Conclusion

Restorative justice offers a path to addressing current conflicts, but also legacies of violence caused by historical phenomena such as colonisation, racism, and patriarchal control. It promotes sustainable and meaningful transformation of the flaws of our societies, enhancing communal healing and relationship building. By shifting from punitive retributive justice systems to victim-centred approaches emphasising forgiveness and healing, restorative justice offers an alternative perspective to mainstream concepts of justice. Its core values – repairing harms and relationships, reintegration, collaboration, healing and accountability – can guide societies towards progress through local communal commitments.

[1] Paraphrased definition from the International Institute for Restorative Practices: https://www.iirp.edu/

[2] Australian Youth Justice Group Conferencing Programme: https://www.justice.vic.gov.au/justice-system/youth-justice/youth-justice-group-conferencing

[3] Pranis, K. (2002). The Little Book of Circle Processes.