In April last year, I arrived in Colombo during the Sinhalese and Tamil New Year celebrations. Three weeks prior to my departure, I had been advised to reconsider my plans to travel to Sri Lanka due to political tensions concerning westerners working with NGO’s, a consequence of the international media attention the Sri Lankan government was receiving concerning the last days of the war.

Undeterred (slightly) by this repercussion, I decided to treat my preliminary plans as a research trip, to further explore the possibilities of creating a series of photographs whilst meeting with people and speaking with them personally about their experiences. It was important to me that I gained a greater understanding of Sri Lanka and it’s history. I have come to comprehend that producing a body of photographic work of any depth is impossible without having a compassionate understanding of its context.

Colombo, Western Province. Families celebrate the Sinhalese and Tamil New Year in the Cinnamon Gardens.

Colombo, Western Province. Families celebrate the Sinhalese and Tamil New Year in the Cinnamon Gardens. Colombo, Western Province. Families celebrate the Sinhalese and Tamil New Year in the Cinnamon Gardens.

Colombo, Western Province. Families celebrate the Sinhalese and Tamil New Year in the Cinnamon Gardens. Colombo, Western Province. Families celebrate the Sinhalese and Tamil New Year in the Cinnamon Gardens.

Colombo, Western Province. Families celebrate the Sinhalese and Tamil New Year in the Cinnamon Gardens.After a few days of finding my feet in Colombo, adjusting to the humidity and constantly reassuring myself that I wasn’t completely mad to be in politically tense country on my own with just 15kg of photography kit to keep me company, I took the train to Batticaloa where I stayed for eleven days. Apparently this is a long time for visitors to stay. I travelled to Batticaloa in particular to meet with women who worked with a community based organisation called Suriya Women’s Development Centre (SWDC).

During my time in Batticaloa I was put through a particularly rigorous vetting procedure. From an outsider’s perspective, it could be said that those working within the realms of peacekeeping and the support of civil society are rather wary and somewhat fed up of westerners with an ‘agenda’. This, of course, is entirely justified. Not only have the people here experienced decades of unrest, they have also had to recover from the tsunami that devastated the area on 26 December 2004. Many an aid agency have come and gone.

Batticaloa, Eastern province. Fisherman on the lagoon, the photograph was taken whilst walking across Kallady Bridge.

Batticaloa, Eastern province. Fisherman on the lagoon, the photograph was taken whilst walking across Kallady Bridge. The only real evidence that it was once inhabited by a busy and thriving community are the foundations of houses and their water wells, the only structures that were not uprooted from the ground by the waves. There are a handful of two- story houses that have been built by those not afraid to return.

The only real evidence that it was once inhabited by a busy and thriving community are the foundations of houses and their water wells, the only structures that were not uprooted from the ground by the waves. There are a handful of two- story houses that have been built by those not afraid to return. The only real evidence that it was once inhabited by a busy and thriving community are the foundations of houses and their water wells, the only structures that were not uprooted from the ground by the waves. There are a handful of two- story houses that have been built by those not afraid to return.

The only real evidence that it was once inhabited by a busy and thriving community are the foundations of houses and their water wells, the only structures that were not uprooted from the ground by the waves. There are a handful of two- story houses that have been built by those not afraid to return. The only real evidence that it was once inhabited by a busy and thriving community are the foundations of houses and their water wells, the only structures that were not uprooted from the ground by the waves. There are a handful of two- story houses that have been built by those not afraid to return.

The only real evidence that it was once inhabited by a busy and thriving community are the foundations of houses and their water wells, the only structures that were not uprooted from the ground by the waves. There are a handful of two- story houses that have been built by those not afraid to return.During my stay in Batticaloa I spoke with some awe-inspiring women, all of different backgrounds and experiences and all of which work quietly and constantly for families in the area, providing support in many different ways. This can range from providing legal support concerning land rights to cultural activities such as workshops in Verbatim theatre. SWDC not only helps individuals, but also other smaller community organisations in the area by helping them find funding to continue operating.

After talking with women involved in SWDC, in particular, Sitralega Maunagurua, the founder of the organisation, I realise that to produce a series of photographs would not be sufficient. The role of education in my practice is important and this is something that I will incorporate into any future projects in Sri Lanka. SWDC is a wonderful example of how cultural programmes can benefit people who need to find a means to express themselves about their thoughts concerning the past, their current situation and hopes for the future.

I left Batticaloa to attend a field trip to Puttalam, which was organised by The National Peace Council. Dr Jehan Perera was kind enough to allow me to tag along to meetings and discussions with various community groups in the area. The National Peace Council with the help of the religious leaders have initiated a language school, where Sinhalese, Tamil and English are taught so that adults and children of different faiths can communicate with each other and work together to ensure a peaceful community.

Puttalam, North Western Province. A meeting with The National Peace Council and local religious leaders to discuss the progress of a new locally initiated language school.

Puttalam, North Western Province. A meeting with The National Peace Council and local religious leaders to discuss the progress of a new locally initiated language school. Puttalam, North Western Province. Dr Jehan Perera, the Director of The National Peace Council.

Puttalam, North Western Province. Dr Jehan Perera, the Director of The National Peace Council. Puttalam, North Western Province. The National Peace Council with the help of local religious leaders have initiated a language school, where Sinhalese, Tamil and English are taught so that adults and children of different faiths can communicate with each other and work together to ensure a peaceful community.

Puttalam, North Western Province. The National Peace Council with the help of local religious leaders have initiated a language school, where Sinhalese, Tamil and English are taught so that adults and children of different faiths can communicate with each other and work together to ensure a peaceful community. Puttalam, North Western Province. Three sisters who run a small women’s centre.

Puttalam, North Western Province. Three sisters who run a small women’s centre.Witnessing these meetings between local religious leaders, local people and those dedicated to supporting them, highlighted the real commitment and fundamental need for communication, so that peace can be guaranteed for future generations.

Puttalam, North Western Province. There are many family run jewelry businesses in the main town, This was taken whilst waiting for the bus to Vavuniya.

Puttalam, North Western Province. There are many family run jewelry businesses in the main town, This was taken whilst waiting for the bus to Vavuniya.From Puttalam I travelled to Jaffna by bus, via Vavuniya. As the bus travelled further north, the roads began to disappear. I was surprised to see many women working on rebuilding the roads. Between Vavuniya and Jaffna the bus stopped at a military checkpoint, myself and one other westerner were asked to leave the bus and were questioned about our visit whilst the bus waited.

The consequences of war are still very visible in Jaffna. Many homes and buildings are in ruins and bullet holes still visible. I found it to be a vibrant place and quite different to the other parts of the country I had experienced. The heavy military presence (and a friendly warning from the guesthouse manager to ‘not get involved in anything political’) did not do much to put me at ease and I stayed for just three days and left feeling unsure of my opinions of the place. Slowly people from the rest of the country are returning as tourists.

The last week of my time in Sri Lanka was spent at a community centre in The Knuckles Mountain Range called Dumbara Gedere, which is run by a Colombo based organisation called Nest. I arrived in the mountains after a few days of travelling by three buses, from Jaffna to Vavuniya to Colombo to Kandy, finishing up with a two hour journey on a tri-shaw. By the end of this trip I had grown accustomed to the Sri Lankan style of driving and could almost sleep through the constant beeping of horns and swerving, go-kart style, around oncoming vehicles.

Nest is an organisation dedicated to promoting understanding within mental health and helps many families and individuals to cope within their communities. Nest was founded by Sally Hulugalle and Kaminia De Soysa in 1987 after they came across an abandoned group of women in need of care at a hospital in 1984. Nest focuses on a range of issues, from providing support to isolated communities, to promoting understanding concerning mental health.

My time at Dumbara Gerere was a reminder that those without a traditional family structure often struggle and there are many problems that affect the Sri Lankan population that aren’t necessarily directly linked to conflict.

Udadumbara, Central Province.

Udadumbara, Central Province.Priyantha Gunasinghe, who runs Dunbara Gedere, with mushrooms that are grown in the community garden.

Udadumbara, Central Province.

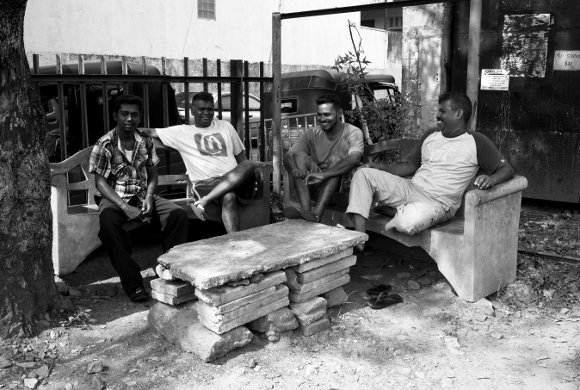

Udadumbara, Central Province.Dumbara Gedere and the people that work there support isolated families in the mountains. It is also a drop in centre for local people.

Udadumbara, Central Province. A local family that live close to the centre.

Udadumbara, Central Province. A local family that live close to the centre. Udadumbara, Central Province. I spent an afternoon with a local school where we played games (it was a Saturday). This photograph was taken a split second before the blue balloon burst. The school was high up in the mountain range.

Udadumbara, Central Province. I spent an afternoon with a local school where we played games (it was a Saturday). This photograph was taken a split second before the blue balloon burst. The school was high up in the mountain range. Udadumbara, Central Province. These boys took time out from playing their game of cricket to pose for a photo.

Udadumbara, Central Province. These boys took time out from playing their game of cricket to pose for a photo. Udadumbara, Central Province. A family home in the mountains.

Udadumbara, Central Province. A family home in the mountains. Udadumbara, Central Province. School children during playtime.

Udadumbara, Central Province. School children during playtime. Udadumbara, Central Province. A farmer tends to his fields in The Knuckles Range.

Udadumbara, Central Province. A farmer tends to his fields in The Knuckles Range.I hope to return to Sri Lanka soon to continue with the portrait series that was published in the first part of this feature. Whilst doing so, I would like to work alongside an organisation, perhaps providing support for a cultural programme that focuses on photography as a means of communication and expression in a post conflict environment.

My time in Sri Lanka has shown me the importance of organisations like SWDC, The National Peace Council and Nest. Communities depend on them to provide unflinching support and understanding. Those who work within these organisations inspire strength in others, either through providing a voice through politics, encouraging reconciliation through the arts, or those who focus on providing a safe community. Local initiatives concerned with encouraging communication are invaluable and provide people of all backgrounds and experiences with hope for their future.